Few fans of The Twilight Zone would downplay the contributions of writer and executive producer Rod Serling. In addition to writing countless classic episodes of the anthology series, Serling also assumed hosting duties when his first choice for the role (actor Richard Egan) proved unavailable. It’s difficult to imagine a version of The Twilight Zone without Serling’s inimitable input, and every subsequent take on the franchise has failed to catch that same lightning in the bottle.

Nonetheless, Serling’s voice was only one of many to inform The Twilight Zone. Some of the original series’ most iconic stories came from elsewhere, from the pens of authors like Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont. Without the input of these lesser-known figures, the classic anthology series would have been deprived of some of its finest installments.

8 “The Last Flight” (S1, E9)

Writer: Richard Matheson

Some of the best episodes of The Twilight Zone explore the concept of time travel. “The Last Flight” focuses on Decker (Kenneth Haigh), a World War One pilot who touches down at an airbase in his own future. Instead of landing in 1917, Decker instead arrives in 1959, much to the confusion of the Cold War-era American officers. However, Decker soon comes to recognize the role that he has to play if history is to stay on track.

Richard Matheson’s debut Twilight Zone episode features a bittersweet resolution and a sensitively written protagonist in the form of Decker. The result is a touching ghost story about duty and sacrifice, representing the best that Serling’s anthology series has to offer.

7 “Two” (S3, E1)

Writer: Montgomery Pittman

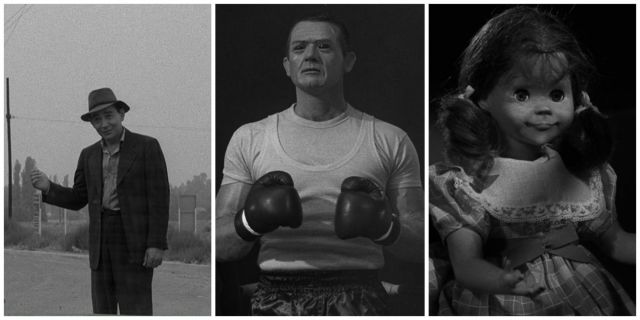

In addition to directing five episodes of The Twilight Zone (including the famous “Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?”), Montgomery Pittman contributed three scripts to the anthology show’s third season. His best, “Two,” kicks off the season with an unlikely love story. A soldier (action star Charles Bronson) explores the ruins of a bombed out city and encounters an enemy combatant (Elizabeth Montgomery). They are the last survivors of a terrible conflict, but will they be able to find peace in the post-apocalypse?

“Two” is an interesting script in that it features little spoken dialogue. As such, the troubled relationship between the former foes is shown through their actions. The man offers the woman food; they bond over beautiful clothes in a shop window; they give into paranoia and hold each other at gunpoint. It’s a tense, almost balletic conflict, but Pittman’s story of love against the odds remains one of The Twilight Zone‘s most iconic romances.

6 “Stopover In A Quiet Town” (S5, E30)

Writer: Earl Hamner Jr.

Long before Greta Gerwig’s Barbie earned praise for its toy-like set design, Earl Hamner Jr.’s “Stopover in a Quiet Town” brought that same sense of shallow unreality to The Twilight Zone. The morning after a night of heavy drinking, Bob and Millie Fraizer (Barry Nelson and Nancy Malone) wake up in an unfamiliar bed. They are fully clothed and confused — just what happened last night, and why are they trapped in a seemingly fake town?

Hamner Jr.’s script makes for entertaining viewing thanks to his snappy dialogue and imaginative flair. Admittedly, it’s possible to see the episode’s twist coming a mile away, but “Stopover in a Quiet Town” is still worth watching. Fans of the episode are also likely to enjoy Rod Serling’s “Where Is Everybody?”, an episode that tackles similar themes, albeit in a very different way.

5 “Steel” (S5, E2)

Writer: Richard Matheson

Of the sixteen scripts that Richard Matheson contributed to The Twilight Zone, Season 5’s “Steel” is perhaps his most underrated. Set in the then-far-off future of 1974, the episode depicts a world where boxing between humans has been outlawed. Instead, contestants use robots to fight one another. Retired boxer Timothy Kelly (Lee Marvin) finds himself in a sticky situation when his outdated robot malfunctions. In order to pay for the repairs, Kelly disguises himself as a robot and enters the ring — but can even a former star survive six rounds with an android?

“Steel” features fewer twists than many entries in The Twilight Zone canon, but its character-driven nature will leave audiences rooting for the underdog. Interestingly, it’s not the only episode of the show to focus on robots in sport: Rod Serling’s controversial “The Mighty Casey” showed how androids might impact professional baseball. Matheson’s script is the better of the two, suggesting that while Serling was the boss, he did not shy away from promoting other talented storytellers.

4 “The Hitch-Hiker” (S1, E16)

Writer: Lucille Fletcher (adapted by Rod Serling)

Don’t be fooled by the fact that the teleplay of “The Hitch-Hiker” is credited to Rod Serling — the Twilight Zone heavyweight didn’t actually come up with the episode’s unforgettable premise. The episode’s key elements (a minor car accident, followed by a character being pursued by a mysterious figure) are present in a 1941 radio play of the same name, written by Lucille Fletcher. Serling adapted Fletcher’s tale for his own series, notably changing the protagonist into a young woman (Inger Stevens), but it was hardly an original idea.

Regardless of the episode’s true writer, it represents a high watermark for The Twilight Zone. Inger Stevens gives a great performance as Nan Adams, a woman whose mounting sense of dread threatens to result in a horrifying revelation. The eponymous Hitch-Hiker (Leonard Strong) is uncannily relentless, while the character’s ominous final line (which can, in fact, be attributed to Serling) is one of the show’s most quotable.

3 “Perchance To Dream” (S1, E9)

Writer: Charles Beaumont

Several of Charles Beaumont’s Twilight Zone scripts have their roots in his earlier short fiction, and “Perchance to Dream” is no exception. Holding the distinction of being the first Twilight Zone episode to be written by someone other than Rod Serling, Beaumont’s tale is surreal and nightmarish. Edward Hall (Richard Conte) is gripped by a terrifying conviction: he will die if he falls asleep. He bases this fear on prior dreams involving a seductive woman (Suzanne Lloyd). If he sees her again, his heart will give out.

Hall’s visit to a psychologist does little to assuage the terror he feels, but his recounting of his nightmares results in some of The Twilight Zone‘s most inventive and dreamlike sets. Beaumont’s script is buoyed by memorable performances (particularly from the beautiful and menacing Suzanne Lloyd), but the strength of his writing showed that the series could benefit greatly from outside voices.

2 “Nightmare At 20,000 Feet” (S5, E3)

Writer: Richard Matheson

Richard Matheson’s most famous script has been the subject of numerous parodies (The Simpsons, The Muppets, and two different episodes of Saturday Night Live), as well as several remakes. The episode is an adaptation of Matheson’s short story of the same name, and concerns a nervous man named Robert Wilson (William Shatner) who becomes increasingly agitated while traveling on an airplane. Wilson believes that the plane is under attack from a hideous monster out on the wing, but no one else believes him.

Wilson’s descent into madness is well handled, with the episode hedging its bets about whether Shatner’s character is really delusional. For fans who are scared of flying, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” is unlikely to cure their phobia, but it does represent one of The Twilight Zone‘s most unforgettable installments. Small wonder, then, that it ranks among the show’s most frequently remade episodes.

1 “Living Doll” (S5, E6)

Writers: Charles Beaumont and Jerry Sohl

Charles Beaumont wrote some of The Twilight Zone‘s most iconic early scripts, including “Perchance to Dream” and “Dead Man’s Shoes.” However, Beaumont’s health drastically declined during the show’s final years, and he was forced to turn to writer Jerry Sohl for support. This partnership resulted in three Twilight Zone scripts, all credited to Beaumont: “The New Exhibit,” “Queen of the Nile,” and “Living Doll.” Of these, “Living Doll” represents the anthology series at its most terrifying.

Terry Savalas plays Erich Streator, a frustrated man who becomes convinced that his step-daughter’s new doll, Talky Tina, is malevolent. His wife thinks he’s crazy; his step-daughter thinks he’s a bully; he thinks that he’s doing what’s right to protect his family. “Living Doll” examines the fault lines in post-war suburban America, but it’s Talky Tina’s creepy voice that will stick in viewers’ minds.

Leave a Reply