Written by Sarcataclysmal

Part 1 | Part 2

So, we’re finally at the end of the first season of LotGH, which is the end of the main series. Gaiden is a series of spin-off prequels focusing on the characters when they were younger (much like Golden Wings was), and it even includes an original arc from chief director Noboru Ishiguro and company.

LoTGH Season 4 (Episodes 87-110)

The end of an era. And by era, I mean the end of Kitty Films as an anime production house. In 1995, the year of season 3’s completion, Kitty Films underwent more changes. As described by JP Wiki: that year, Kitty Enterprise (a subsidiary of Kitty Films) was acquired by PolyGram Corporation. Kitty Films was also separated from the Kitty Group, and then three more of the company’s producers left the company: Kei Ijichi, Junpei Nakagawa, and Masatoshi Tahara. The three founded a production company called K-Factory together, and that’s where management of Legend of the Galactic Heroes (and I believe a few other titles) was transferred to. Other series were transferred to VAP and Pony Canyon.

K-Factory, unlike its predecessor, however, did not have its own in-house animation team (referencing Kitty Films Mitaka Studio). That means that K-Factory had to do more than just outsource the animation elsewhere, they’d have to outsource pretty much the whole production elsewhere. This puts even more stress on Artland and Magic Bus, and so they’d have to divvy up the production even more.

First things first: Shimizu returned for all three of his position (character designer, chief animation director, and ‘director’); Ishiguro returned as chief director; Kawanaka returned as the scriptwriter, and Masatoshi Tahara rejoined the LotGH production as series director (this time under his real name). Also worth mentioning: because the series could no longer be centralized to Magic Bus, founder Satoshi Dezaki, who was credited as production manager for LotGH seasons 2 and 3, seems to have relinquished that title.

So, that’s where my bonus of part 3 comes in. Instead of Magic Bus and Artland co-producing the series by rhemselves, SHAFT was brought on as well. The three would take turns animating one episode each, and only two episodes are exceptions to this: episodes 100 and 106, which should have been given to Artland but were instead produced over at Mushi Production. They worked on a few of SHAFT’s episodes prior, and SHAFT was founded by former Mushi Production staff, so that might be where the connection comes from, but take that with a grain of salt as I didn’t look too deeply into all of the staff involved.

How do we know there was more of a workload on the studio’s plates this time around? Well, we’re going to look at three credits: 制作進行 (assistant production manager), 制作担当 (production manager), and 制作デスク (production desk). So, let’s first define these: a production manager normally works across all, or most, of a series– they’re the lead manager, in a way. Under the production manager are assistant production managers, and they’re in charge of specific episodes. Production desk’s job isn’t necessary to tell but just think of it as in the same realm.

So, production managers usually belong to the main studio producing sometimes, or occasionally if a whole episode is outsourced it’ll be someone from there. And assistant production managers usually came from the main studio, but sometimes they’re from another studio that did a significant amount of work on an episode (whether or not they’re credited as such). Some of the episodes SHAFT worked on in season 3, for example, credit Mitsutoshi Kubota as an assistant production manager, but they were never fully in charge of an episode’s production. Instead, the production manager was usually someone from Magic Bus or Artland. In season 4, however, Kubota is credited as an assistant production manager, production manager, and production desk for all of SHAFT’s episodes– meaning they took full (or most of) the responsibility for the production of those episodes.

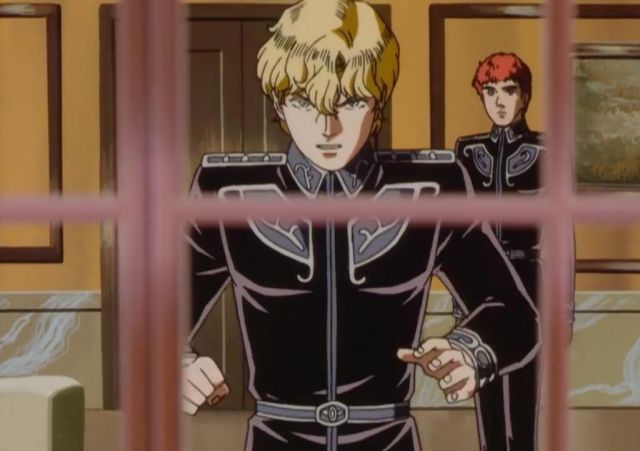

While I’d like to say that this season looks worse due to the production issues… it actually looks a lot better, somehow. The opening episode of the season, episode 87, was produced at SHAFT, and there’s a noticeable consistency to its animation direction, and although previous episodes have had beautiful background art and some clean compositing (occasionally; there’s lots of weird gradient usage), this first episode is very strong in its animation. Episode 88, produced at Artland, looks about the same as previous seasons, but still somewhat more consistent. And then, there’s episode 89, arguably the most refined episode in the entire series, produced at Magic Bus. Remember Yuuji Ikeda? Yeah, he was the animation director for this episode, and you can tell from its shoujo-looking characters. Here, though, that’s a good thing– it fits the narrative. Shimizu himself storyboarded the episode too, and not only that, for this episode, as well as the rest of Magic Bus’ episodes, he served as layout supervisor (meaning he directly supervised the layouts in the key animation process). That, of course, means you get incredible-looking shots like this.

There’s one other episode I’d like to talk about in particular. That would be SHAFT’s episode 108, the climax of the season. It’s not the most lavishly animated, from what I can remember, nor does it one-up episode 89 in terms of sheer Dezakian beauty, but it’s certainly ambitious. Now, I have a lot of staff to talk about here because of me being me, so let’s get through that quickly.

The episode was directed Takashi Asami (who directed their previous episodes) and storyboarded by Toshimasa Suzuki, and most people know him probably for his works with Xebec as director of Heroic Age (with Takashi Noto) and Lagrange: The Flower of Rin-ne (with Tatsuo Satou), but not many people know that Suzuki was employed by SHAFT from ~1990 to 2000.

Although he no longer is employed by the studio, he still does work for them as a freelancing director, such as being a unit director on two of the three Kizumonogatari films.; most recently, he storyboarded the first and final episodes of Magia Record in 2020. Jou Tanaka, a common collaborator of SHAFT who did the animation direction for all of their previous episodes, did that here too.

The episode does have a few notable names from their animation talents, too, though. Employed by them at the time: Yoshiaki Itou (Hidamari Sketch character designer), Hitoshi Hibino (color designer for a large number of their works), Makoto Kohara (current CEO of studio Diomedea), and Natsuko Fukuhara (a board member since 2007). Not employed by them: Nobuyuki Takeuchi, a production designer for most of Monogatari and chief director on Sarazanmai. So that’s pretty stacked in retrospect.

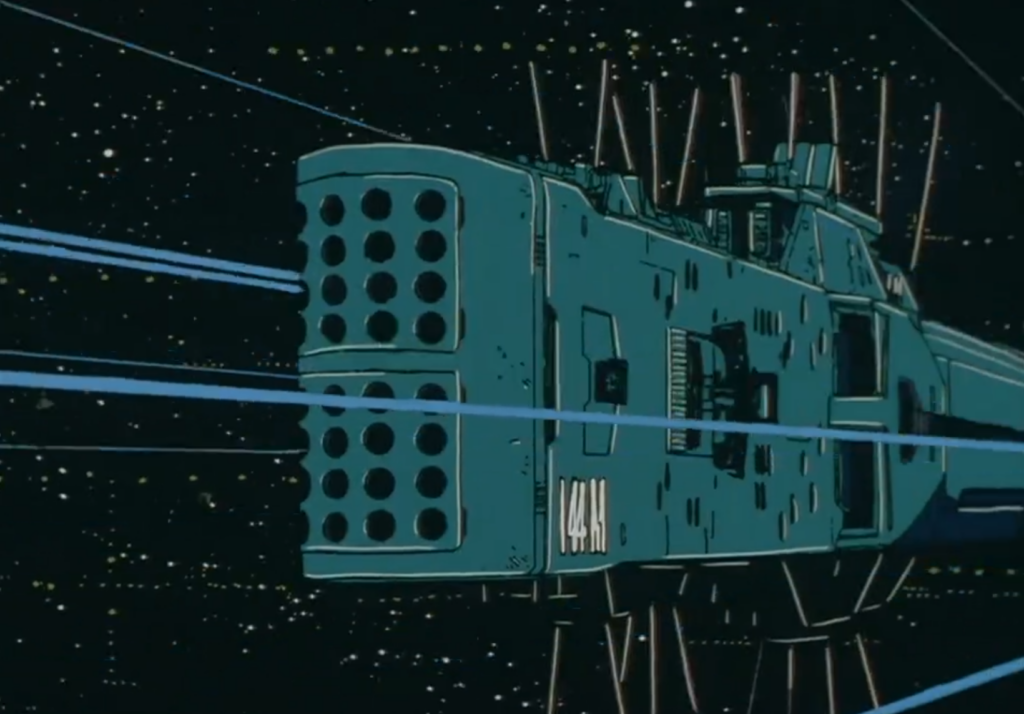

As to why this episode is so striking to me, and why I think it’s ambitious, it does basically the opposite of episode 89. Whereas 89 represents beauty, peace, and warmth, 102 is about war, destruction, and a battle between ideologies. There are shots of a ship crashing into another ship (and then entering that ship), all sorts of other mechanical animations; lots of death, destruction, ambitious camera angles for some fights, and some consistent animation direction.

The series finishes off under Keizou Shimizu’s supervision, and as finales go, it’s probably one of the best you’ll ever get.

Gaiden (1998-2000)

There isn’t much about these episodes anywhere. I looked through a few of the credits, but not nearly enough to say a whole lot, but I’ll say what I can.

Gaiden 1 (sometimes called A Hundred Billion Stars, A Hundred Billion Lights) was outsourced to all 4 studios from season 4, but in a much more wacky order. Episodes 1-4, 13-14, 20, and 24 at Magic Bus; episodes 5-8 and 17 at SHAFT; episodes 9-12, 16, and 21-23 at Artland; and episodes 15 and 18-19 at Mushi Production. There are some really good-looking episodes, some visual experimentation, and then there’s a lot of inconsistency. It’s to be expected. Kawanaka came back to write the scripts, and Ishiguro returned as chief director. Episodes 1-4 also had Keizou Shimizu credited as director, and episodes 5-8 had Asami Ryuu (笠麻美; a pseudonym of someone working at/with SHAFT) directing. Shimizu also served as character designer, and he did chief animation direction for episodes 1-4 and 13-24. SHAFT associate Jou Tanaka did layout supervision for episodes 6-8, Mitsutoshi Kubota served as production producer (essentially ‘animation producer’) for episode 17, and that’s about all I can really say when it comes to LotGH Gaiden.

Gaiden 2 (sometimes called Spiral Labyrinth) was chief directed by Ishiguro and directed by Shimizu; the scripts were written by Kawanaka and Kazumi Koide (writer of Golden Wings); and the character designs were done by Yuuji Ikeda and Katsumi Michihara. Shimizu served as chief animation director for episodes 1-14, 16-17, 19-23, and 27-28, and one episode had someone else, that being episode 25 which had Kenichi Imaizumi (Kingdom Season 3 director) as CAD. The animation was produced only at Magic Bus (episodes 1–14, 16–17, 19–23, 27–28) and Artland (episodes 15, 18, 24-26), and based on what I just told you I’m sure you can assume that it’s a much more inconsistent season despite there only being two studios this time around. Again, that’s really all I can say, as the information regarding Gaiden isn’t readily available.

Final LotGH Production Notes

In an interview from 1996, Yoshiki Tanaka (the novel’s author) expressed his disbelief when he found out that there were plans to produce an anime series based on his novels from Masatoshi Tahara. Tahara had, from the very start, intended to adapt Tanaka’s entire novel, which he knew would take more than a hundred episodes, and again why Tanaka expressed so much disbelief over the idea. He was very passionate about his desire to adapt Tanaka’s novels onto the screen. Tahara states in the same 1996 interview that the idea to use classical music for the series was something that Takeshi Shudou, the scriptwriter for the first film, had come up with. According to Shudou, he just wanted one specific scene in the first few episodes to use “Boléro” by Maurice Ravel, and eventually, director Ishiguro decided to use classical music for the entire anime. Thus why most of the series credits Shinsuke Kazato and VEB Deutsche Schallplatten for the soundtrack. VEB Deutsche Schallplatten, for those who don’t know, was the sole record label in the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) until its demise in 1990 (with the fall of the Berlin Wall, and East/West Germany). Noboru Ishiguro, in an interview listed on the series’ official website, notes how hard it was to produce a series over the course of about 13 years with more than 130 voice actors– and, I have to say, for the 1980s and 90s, that is an exceptional amount of people to give jobs to, and to manage accordingly. Unfortunately, however, not everyone would be able to see the series fully through. Kunichika “Kei” Tomiyama, voice actor for Yang Wen-Li, passed away on September 25, 1995, three years before the end of the main series.

Legacy

Legend of the Galactic Heroes has left a standing legacy in otaku culture, whether it’s the novel or the anime we’re talking about. Ollie Barder, writing in Forbes, in his review of the first translated novel released in 2016, calls it a series that “needs to be read.” Rachel Cordasco of Focus Magazine calls the novels the sci-fi equivalent of Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; and writers from Anime News Network and Otaku Magazine have referred to the anime series as having “one of the most satisfying… endings ever written” and “anime’s greatest sci-fi epic”, respectively. Michael S. C. Tse and Maleen Z. Gong, in an academic work titled “Online Communities and Commercialization of Chinese Internet Literature”, mention the novel’s grand influence over the development of online Chinese literature.

Its effect on anime and otaku culture is also evident. SHAFT, in 2008, produced a series titled Maria Holic, and in it: none other than a blatant (humorous) reference to the series in its sixth episode. A 2000 anime series titled Mutekiou Tri-Zenon created by E&G Films (who co-produced two episodes of the first season) has a strangely familiar blonde character. A few times, Yang Wen-Li’s name appears on a mug in the manga Nichijou, as well. The references are abundant is what I’m getting at. Of course, since 2018, Production I.G has been re-adapting the LotGH series with modern animation, and the third season of that (which is really three movies) is set to premiere in 2022, which has added to the reinvigorated interest in the series by both western and eastern audiences. It’s not a totally accurate adaptation like the original, but it doesn’t have to be and it’s not trying to be. To say the least, though, Legend of the Galactic Heroes has had a lasting impact.

Research assistance by Slad.

Written by Sarcataclysmal

Visit Legend of the Galactic Heroes official website.

You can watch both the LoTGH OVA anime series on HiDive.

©Yoshiki Tanaka, Tokuma Shoten, Tokuma Japan Communications, Wright Staff, Suntory

Leave a Reply